As I prepare for my upcoming voyage on MS Spitsbergen, a journey from Bergen, Norway, along the Atlantic coast down to West Africa, exploring Cabo Verde and the Bijagos archipelago, I can’t help but reflect on the greatest voyages of exploration, one that not only defined my field of study but also shook the world’s beliefs to their core. Admittedly, it feels like I’m a bit late to the party once again.

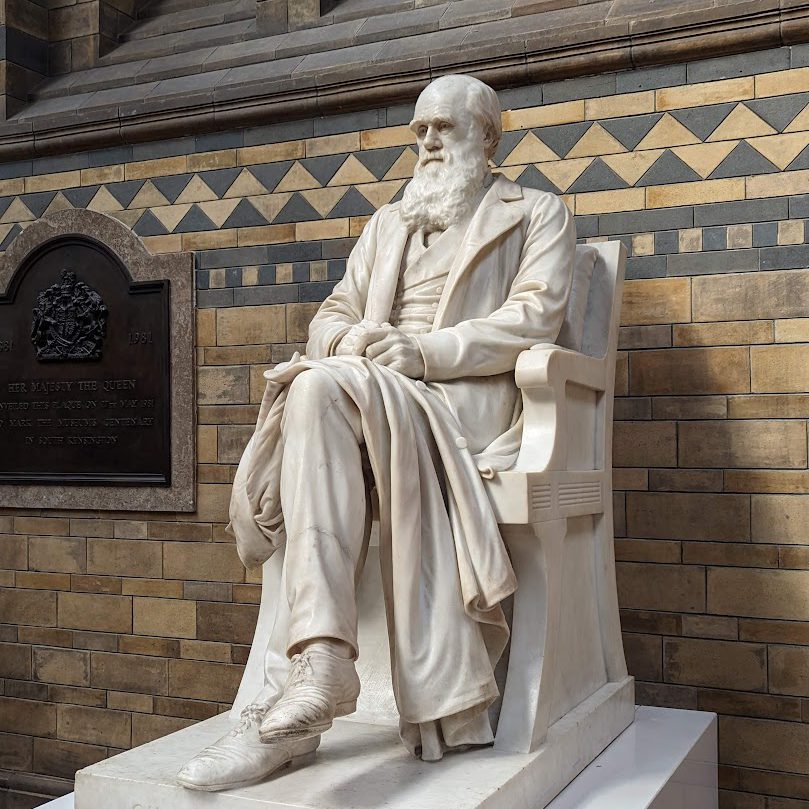

The world has undergone seismic shifts since Charles Darwin set sail on the HMS Beagle in 1831. His voyage would ultimately reshape our scientific understanding, but it also marked the twilight of the old naturalists, ushering in a new era of biological exploration. In today’s modern world, where information flows like a river, our approach to exploring and understanding nature has transformed profoundly.

Similar to the evolution of Darwin’s finches, natural selection has led to the speciation of anole lizards adapted perfectly to the different islands in the Caribbean.

Paradigm Shifts

Once upon a time, the great explorers and naturalists of the Age of Enlightenment embarked on daring expeditions into uncharted territories. Armed with boundless curiosity, unwavering spirit, and an insatiable thirst for the unknown, these pioneers were not just observers of nature’s wonders; they were the architects of scientific discovery.

However, as the world raced forward, it seemed to shrink in some inexplicable way. The unrelenting pace of life quickened, and the old naturalists, once a thriving breed, found themselves struggling to keep pace with the rapidly changing landscape of scientific exploration. The era of the solitary observer, who meticulously recorded every intricate detail based on a lifetime of experience, was slowly giving way to a new paradigm.

Here and now, we find ourselves in the age of the new naturalists—modern explorers armed with smartphones, cameras, and an unquenchable curiosity. They aren’t satisfied with passive consumption of information; they actively engage with the natural world.

In our digital age, technology plays a pivotal role, both challenging and empowering these hobby naturalists. With their devices in hand, they not only capture the breathtaking beauty of nature but also document its phenomena, sharing their discoveries passionately with a global audience.

Amidst this flood of data from digital naturalists, one question looms large: How do we manage this deluge of information? Here’s where technology’s magic comes into play. It transforms this torrent of data into structured, standardized information—a treasure trove of knowledge. This vast pool of data, meticulously gathered by enthusiasts worldwide, underpins cutting-edge scientific research.

Tackling the Unknown

Since its launch in 2008, iNaturalist has stood at the forefront of this digital revolution in naturalism. Much like the computer vision model identifying species from images, iNaturalist now introduces the Geomodel—a marvel of deep learning. Unlike its visual counterpart, the Geomodel takes geographic locations as inputs and predicts the most likely species inhabiting those areas.

Introducing the iNaturalist Geomodel!

— iNaturalist (@inaturalist) September 21, 2023

Read more about how we're using it to improve Computer Vision suggestions on our blog https://t.co/k2scm1pvCb pic.twitter.com/1QFsoL8uDk

The Geomodel’s uniqueness lies in its ability to harness collective observations. It leverages a global community of naturalists, each armed with a smartphone and a keen eye for nature, to predict species’ presence in specific locations—a testament to the powerful synergy between citizen science and cutting-edge technology.

But where does the Geomodel fit into the broader context of biodiversity knowledge? It tackles one of the seven shortfalls that have plagued our understanding of biodiversity, as highlighted in the publication “Seven Shortfalls that Beset Large-Scale Knowledge of Biodiversity” [Hortal et al. 2015]. Specifically, the Geomodel makes significant strides in mitigating the “Wallacean shortfall of knowledge,” addressing the challenge of accurately predicting the geographical distribution of many species.

The Geomodel goes beyond mere species identification. It enhances the accuracy of computer vision suggestions, transitioning from grid-based observations to a future where geospatial information is fast and accessible. This means that mobile apps can now offer in-camera suggestions and display taxon maps offline, liberating nature enthusiasts from the constraints of a constant internet connection.

The significance of the Geomodel extends further—it serves as a tool to spotlight unusual observations. In an ever-evolving natural world, these peculiar sightings could signify misidentifications or groundbreaking discoveries—a potential new species, an extended range, or the early detection of an invasive species. The Geomodel’s ability to rank observations by their geographic uniqueness promises to deepen our understanding of the natural world.

In the realm of conservation, the Geomodel provides a potent instrument for assessing the geographic range size of species—a critical factor in conservation efforts. It empowers land managers to allocate resources and attention, focusing on small-range species facing a higher risk of extinction.

In the age of the sixth mass extinction, where biodiversity teeters on the brink, the recording and study of nature’s intricacies assume paramount importance. As species vanish before our eyes, each data point recorded by new naturalists contributes to a broader understanding of ecosystems and informs critical decisions about conservation efforts.

Embracing the era of the new naturalists involves acknowledging the pivotal role of technology in reshaping the field. The Geomodel, a living embodiment of this transformation, bridges the gap between citizen science and data-driven insights. It empowers individuals to connect with nature, contribute valuable data, and collectively unveil the mysteries of our ever-changing world.

The old Naturalists are dead – Long live the modern Naturalists?

“Freedom of thought is best promoted by the gradual illumination of men’s minds, which follows from the advance of science.”

Charles Darwin

In true Darwinian spirit, it’s essential to exercise caution when wielding such powerful tools. Just as Darwin meticulously weighed the implications of his groundbreaking theory of evolution by natural selection, we must consider the consequences of our digital discoveries. The profound nature of these revelations has the potential to reshape our understanding of the natural world and our interactions with it.

Darwin would likely view these developments as valuable for advancing our understanding of biodiversity and natural history, as he advocated using the best available tools for scientific research. He would appreciate the ability of iNaturalist and other citizen science initiatives to engage a broad community of observers and promote the study of the natural world, aligning with his passion for exploration and scientific inquiry. Darwin would also recognize that iNaturalist, like any scientific endeavour, has limitations and challenges, including data quality, biases in observation, and the need for expert validation of identifications.

And so, we stride forward into an era where, in the footsteps of the old naturalists and equipped with a passion for nature, anyone can make a difference, irrespective of their background, but always mindful of the profound implications of their discoveries.